The Debates in Archaeology Annual Symposium was launched in 2019 with the idea of attracting top scholars for debates about contemporary topics in the world and the world of archaeology.

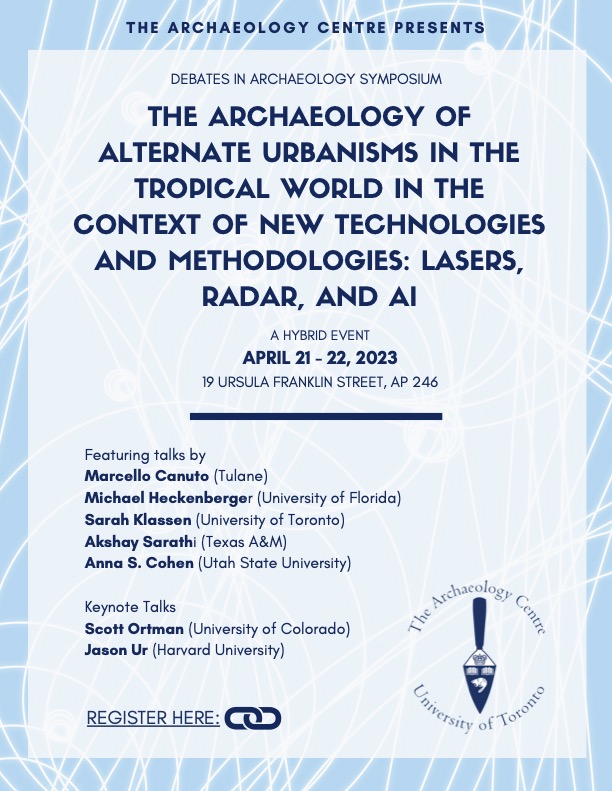

The 4th Annual Debates in Archaeology Symposium

April 21 & 22, 2023

Theme: “The Archaeology of Alternative Urbanisms in the Tropical World in the Context of New Technologies and Methodologies: Lasers, Radar, and AI.”

Organizers: Sarah Klassen (University of Toronto)

Friday, April 21st: 3:00 pm to 5:00 pm. Keynote lecture by Scott Outman. Then, 5-10 minute panelist flash talks followed by discussion.

Saturday, April 22nd: 10:00 am to 4:00 pm. Three sessions (with breaks) including 20-25 minutes talks with discussion.

This conference will be hybrid. For in-person: 19 Ursula Franklin Street, AP 246. Registration is required for those attending online. You can register once for both days of the conference. Please click here. You can download the schedule and abstracts of the talks below.

Information:

Archaeologists have long doubted that tropical environments could sustain large-scale urban complexes or extended, intensive agricultural systems in pre-modern times. However, compelling evidence is emerging that complex social formations flourished in densely vegetated or re-engineered tropical ecosystems. Across the globe in tropical forest environments, archaeologists have identified the material correlates for early urbanism, domestication, intensive and extensive agriculture, and infrastructural development on a scale that rivals the urban landscapes of non-tropical regions.

In recent years, remote-sensing techniques, including lidar and ground penetrating radar, have revolutionized our understanding of preindustrial urbanization and imperial expansion in tropical and non-tropical environments (Canuto et al. 2018; Heckenberger et al. 2008; Klassen et al. 2021; Sarathi (ed) 2018; Ur 2010). New developments in artificial intelligence and novel approaches such as settlement scaling have also significantly advanced our analysis of these processes (Ortman et al. 2015).

The invited Keynote speaker and 5 panelists will debate whether preindustrial urbanism in tropical forest ecologies share unique structures, institutions, landscapes, and historical trajectories, and they will evaluate in turn how urban polities in the tropics compare with cities and hierarchical social formations that developed in other regions of the world. For instance, does low-density urbanism constitute a common feature of cities in tropical environments, and how can we explain alternate settlement systems and historical variations in the social and economic organization of green cities? As a corollary, what generalizations can be made about tropical urban landscapes in terms of neighborhood associations, urban planning, investments in infrastructures, and the integration of cities in larger political systems?

In addition, speakers will assess the contributions and limitations of new technologies in the study of tropical urbanism, including lidar and AI. In the end, the talks will present a variety of case studies of alternate urban political orders from tropical climates across the world.

References:

Canuto, M.A., F. Estrada-Belli, T. G. Garrison, S. D. Houston, M. J. Acuña, M. Kováč, D. Marken, P. Nondédéo, L. Auld-Thomas, C. Castanet, D. Chatelain, C. R. Chiriboga, T. Drápela, T. Lieskovský, A. Tokovinine, A. Velasquez, J. C. Fernández-Díaz, and R. Shrestha (2018). Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala. Science, 361.

Heckenberger, M., Russell J.C., Fausto, C., Toney, J.R., Schmidt, M.J., Pereira, E., Franchetto, B., and A. Kuikuro (2008). Pre-Columbian urbanism, anthropogenic landscapes, and the future of the Amazon. Science, 321.

Klassen, S., Carter, A., Evans, D., Ortman, S., Stark, M., Loyless, A., Polkinghorne, M., Heng, P.,Hill, M., Wijker, P., Niles-Weed, J., Marriner, G., Pottier, C., and R. Fletcher (2021). Diachronic modeling of the population within the medieval Greater Angkor Region settlement complex. Science Advances, 7 (19).

Sarathi, A. (ed) (2018). Early Maritime Cultures on the East African Coast and the Western Indian Ocean. Archaeopress, Cambridge.

Ur, J. (2010). Cycles of Civilization in northern Mesopotamia, 4400-2000 BC. Journal of Archaeological Research, 18 (4).

Keynote Speakers

Scott Ortman (University of Colorado)

Jason Ur (Harvard University)

Panelists

Marcello Canuto (Tulane)

Michael Heckenberger (University of Florida)

Sarah Klassen (UofT)

Akshay Sarathi (Texas A&M)

Anna S. Cohen (Utah State University)